Trends in Remote Work

The COVID-19 pandemic, though it was a public health crisis, also changed the way Americans work and travel. One of the long-lasting impacts of the pandemic is the shift in the number of American workers who do their job remotely. As the pandemic recedes from people’s minds, many businesses and workers are still grappling with its implications on the future of remote work. This blog summarizes the latest data and research in this area.

Who Can Work Remotely?

It is important to differentiate between remote work from a technical standpoint and remote work as a corporate policy. The two are related, but not the same.[1]

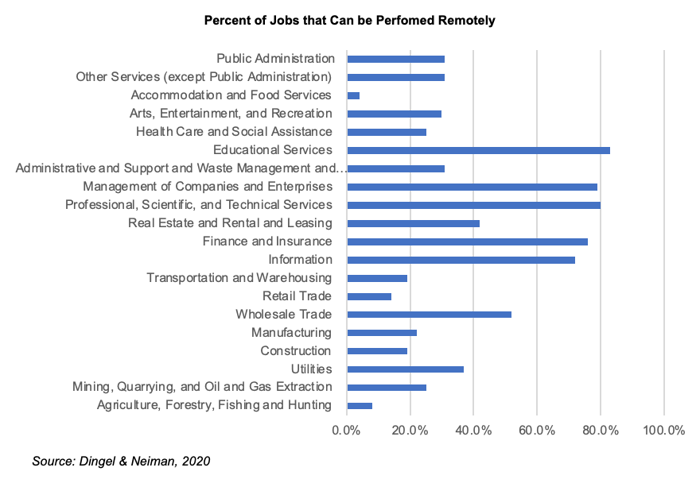

Since the breakout of the pandemic, considerable research has been conducted to understand what type of jobs can be done remotely from a technical perspective. One of the most widely cited research articles was conducted by Dingel and Neiman (2020).[2] Analyzing O*Net data for different activities and tasks, they identified the occupations that can be performed remotely. Then, they computed the percentage of remote jobs for different industries. They estimated that 37% of national jobs can be conducted remotely, but the rate varies by region and industry. Not surprisingly, many office-based industries, such as professional and technical services; financial services; and educational services, have the highest percentage of jobs that can be done remotely. Non-office-based industries, such as agriculture; forestry, fishing, and hunting; retail trade; and construction, have a low percentage of jobs that can be performed remotely.

Similarly, a McKinsey study completed around the same time analyzed different tasks and activities of over 800 occupations, and estimated the maximum percentage of workers that can perform their duties remotely for different industries.[3] Their study estimates that about 46% of U.S. jobs have the potential to be done remotely. In terms of industry differences, they reached similar conclusions as the Dingel and Neiman (2020) paper: financial and professional services are the industries with the highest percentage of workers capable of being remote, while agriculture, construction, and food services have the lowest percentage of jobs that can be accomplished remotely.

Who Are Working Remotely?

Just because one job can be done remotely, however, does not mean the individuals doing that job will work from home. The number of people working remotely also depends on other factors, such as workplace policies, which can differ significantly even for businesses in the same industry. Further, macroeconomic conditions, labor market competition, and public policies can influence individuals’ decisions to work from home.

For example, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the degree and the nature of infectiousness of the virus were not known, so many states implemented “stay-at-home” policies during the spring of 2020, and only essential workers were allowed to work onsite. As a result, the number of remote workers soared. In 2021, despite the receding pandemic and wide availability of COVID-19 vaccines, a widespread labor shortage led many companies to maintain flexible work from home (WFH) policies to retain and attract workers. With economic growth slowing and concerns of a recession looming since 2022, more companies are requiring their employees to work onsite, even if those positions can be performed remotely from a technical perspective.

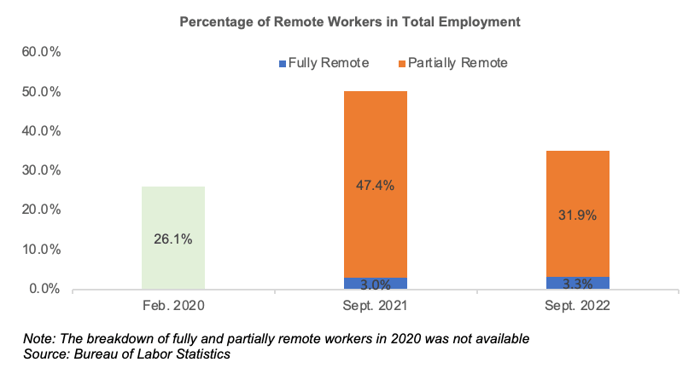

In terms of the number of workers actively working remotely, data from the BLS showed that in September 2021, 50.4% of private employment in the nation were fully or partially remote. This number declined to 35.2% in September 2022, but was still higher than the 26.1% reported in February 2020 before the pandemic.

The BLS data show that, as of September 2022, of all remote jobs, only a little over 10% were fully remote, indicating that businesses overwhelmingly selected hybrid work arrangements. Indeed, the hybrid work model combines the benefits of both work from home and onsite. It grants employees more flexibility, reduces commuting time and costs, while also preserving the benefits of face-to-face interactions and communication that make work onsite more efficient. It is not surprising that it was embraced by most businesses that allow remote work.

A closer look at BLS data indicate that smaller businesses tend to allow more fully remote work arrangements than larger companies.[5] There could be multiple reasons. When businesses start up, they may lack capital to rent or purchase office space, thus allowing fully remote work can result in significant cost savings. Smaller companies are also more likely to offer fully remote work as a benefit, if they perceive that they are not competing with larger corporations in offering salaries and other benefits such as health insurance. Research shows that employees value the option of working from home. Even 2 to 3 days of WFH is worth 5% of pay, with even higher valuation for women, workers with children, and those with long commutes.[6] Thus, allowing remote work can be a powerful tool for recruiting and retention.

Where is the Sweet Spot?

While hybrid work arrangements are hugely popular, there remains the question of how many days to allow employees to work from home, which can range from one to four days a week.

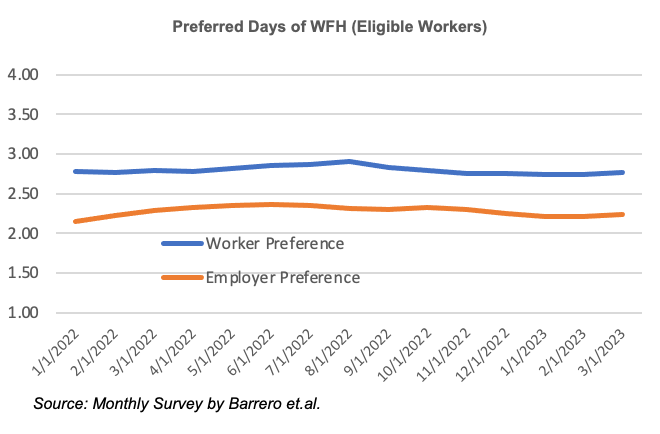

Researchers at Stanford University and the University of Chicago have conducted monthly WFH surveys since 2020 to track the changes in workers’ and employers’ attitudes toward WFH.[7] Their data since 2022 show a consistent trend related to preferred days of WFH. For employees who can work from home, they do not prefer the maximum days of four or five. Instead, they prefer about 2.8 days per week to work from home. This suggests that employees also recognize benefits of onsite working, such as efficiency, team collaboration, and socialization with colleagues.[8] The average days of WFH preferred by employers is 2.3 days per week. While this is lower than what workers desire, it shows employers are willing to accommodate workers’ needs for flexibility.

Future WFH and JobsEQ

The percentage of remote workers has declined significantly since the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. This percentage will likely continue to decline, but many experts believe that the percentage will not fall to the pre-pandemic levels. This is because some of the workplace policies developed during the pandemic are likely to persist. Some reasons include new investments in physical and human capital during the pandemic that enable remote work to be more efficient, diminished stigma associated with remote work, and a pandemic-driven surge in technological innovations that support remote work.[9] More importantly, employees have benefitted considerably from remote work, and they will continue to support policies that allow more flexibility. As a result, many experts expect that this percentage will stabilize to a level that is higher than the pre-pandemic levels in the near future.

Still, the overall changes in the economy and labor market may affect the number of remote workers. With the possibility of a recession, the number may be lower while the percentage will be higher due to a labor market shortage.[10] In the long-term, one major factor that will affect remote work is the technological advances that make it feasible to perform more tasks remotely. The recent explosion of artificial intelligence (AI) technology will also impact remote work in the future.

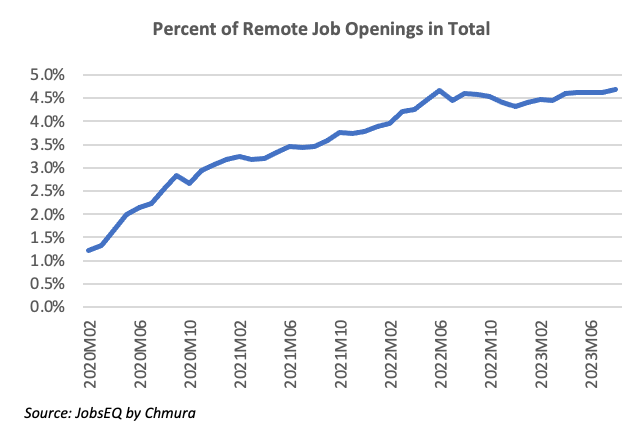

Due to heightened interest in remote work, Chmura is working to incorporate remote work information in its JobsEQ© technology platform. Currently, in its Real Time Intelligence (RTI) data, there is an indicator for remote work, collected from job advertisements. As the chart shows, the percentage of jobs vacancies that are remote increased steadily from early 2000 to mid-year 2022, due to pandemic concerns and ensuing labor shortage. It dipped slightly in the second half of 2022 but remains at an elevated level. While this indicator only reflects whether a job can be remote for currently open positions, not the overall workforce, its change over time allows us to gauge the trend in remote work in the labor market.

--------------------------------------------

[1] In this blog, remote work and work from home (WFH) are used interchangeably.

[2] Jonathan Dingel and Brent Neiman, “How Many Jobs Can Be Done at Home?”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, June 2020, accessed April 26, 2023, https://www.nber.org/papers/w26948

[3] Susan Lund, Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika and Sven Smit, “What’s Next for Remote Work: An Analysis of 2,000 Tasks, 800 Jobs and Nine Countries,” McKinsey Global Institute, November 2020, accessed May 3, 2023, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics, "2022 U.S. Business Response Survey on Telework, Hiring, and Vacancies”, accessed July 20, 2023, https://www.bls.gov/brs/

[5] Ibid.

[6] Aksoy, Barrero, Bloom, Davis, Dolls and Zarate, “Working from Home Around the Word”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, August 2022, accessed July 19, 2023, https://wfhresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Working-from-Home-Around-the-World-23-August-2022.pdf

[7] Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, 2021. "Why working from home will stick," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731.

[8] Gwynn Guilford, “Option to Work from Home Disappears”, Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2023.

[9] Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven Davis, “Why Working From Home Will Stick?”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28731. Accessed April 26, 2023, https://www.nber.org/papers/w28731

[10] Michael Cui, Janet Bush and Nicholas Bloom, “Forward Thinking on How to Get Remote Working Right with Nicholas Bloom”, McKinsey Global Institute, January 2023, accessed May 3, 2023, https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/forward-thinking/forward-thinking-on-how-to-get-remote-working-right-with-nicholas-bloom

Subscribe to the Weekly Economic Update

Subscribe to the Weekly Economic Update and get news delivered straight to your inbox.