What is the Supply Chain and How Does it Affect Me?

Most Americans have heard more about the supply chain in the past few months than they wanted. Stories about people not able to find PlayStation 5s or waiting more than six months for delivery of a new sofa are common, and we are told supply chain disruptions are to blame. But what does it actually mean to say that the supply chain is disrupted? What are the causes of the disruption, and how does it affect the broader economy? This blog discusses these issues and uses JobsEQ by Chmura® data to illustrate the role labor shortages play in critical occupations in our current woes.

Causes

The strains on the supply chain began in the earliest days of the pandemic. Fearing a long recession in which consumers drastically reduced their spending, many businesses scaled back their production. This strategy proved to be a miscalculation because the demand for some goods increased dramatically in the United States. Maybe you bought yourself exercise equipment or undertook a do-it-yourself home improvement product. If you did, you were not alone. Unwilling to take vacations, eat out, and make use of other services, U.S. consumers shifted their attention to purchasing goods. E-commerce in 2021Q1 increased 39% compared to 2020Q1.[1] Out-of-stock messages for virtual purchases have risen 32% since June.[2]

The irony is that global, as opposed to United Stated, demand is largely unchanged from pre-pandemic levels. Ocean liner company Maersk estimated that global shipping demand was up only 2.7% in 2021Q2 compared to 2019Q1.[3] If shipping and infrastructure capacity could be moved to where demand is greatest, it would significantly alleviate supply chain woes—but of course, one cannot pick up and move a port or a fleet of trucks from country to country.

"Logistics companies were not able to scale up their labor force quickly enough to meet rising demand."

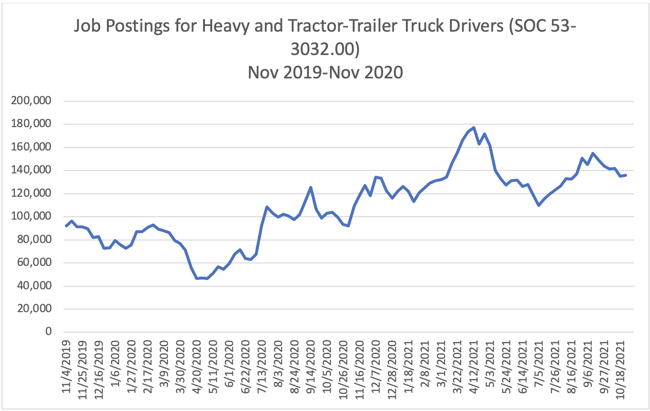

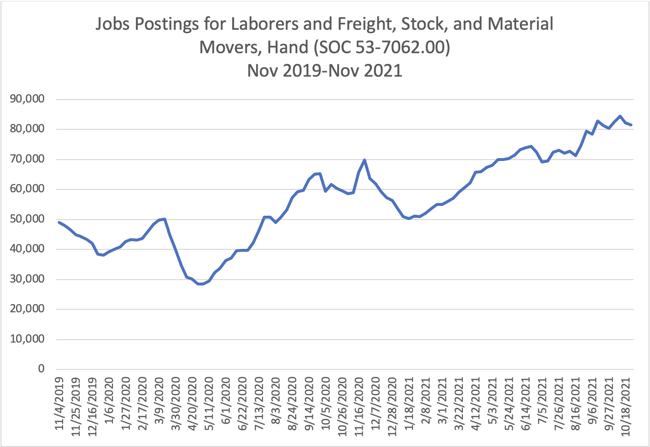

An increase in demand requires a corresponding increase in the labor force in logistical occupations. A strong logistics network ensures that both parts required to manufacture goods and finished products arrive where they need to be in a timely fashion. Logistics companies were not able to scale up their labor force quickly enough to meet rising demand. Two occupations that illustrate the problem are Heavy and Tractor-Trailer Truck Drivers (SOC 53-3032.00) and Laborers and Freight, Stock, and Material Movers, Hand (SOC 53-7062.00). In the United States, truck drivers are the primary movers of parts to manufacturers and finished goods to retail locations and warehouses. For years industry leaders worried about a shortage of truck drivers, worries that manifested with the increase in demand.

JobsEQ job posting data are a good proxy for occupation shortages. Companies facing a worker shortage are more likely to advertise for positions to fill the shortage. Nationwide, active job postings for truckers have increased from roughly 90,000 per week in February 2020 to roughly 135,000 per week in late October 2021.

Laborers are necessary to unload cargo ships, railroad cars, and trucks. Companies posted approximately 80,000 active job advertisements for Laborers and Freight, Stock, and Material Movers, Hand (SOC 53-7062.00) in late October 2021, compared to approximately 45,000 in February 2020.

Even Santa is having a hard time finding enough elves.

Capacity issues have also plagued the supply chain in the United States. The demand increase requires more ships to transport parts and goods across oceans, but shipping capacity is largely equal to pre-pandemic levels.[4] Ships need containers to transport cargo, but the industry faces a container shortage and the unique problem that too many empty containers are stranded thousands of miles from where they are needed.

As the demand for products has increased, so too has the burden placed on the country’s transportation infrastructure. If ships cannot dock and unload at harbors, the parts and finished goods they carry are out of circulation, causing further backups. Due to labor and capacity issues, most major ports are overwhelmed, with as many as 96 ships anchored at sea because the Port of Los Angeles is unable to unload them.[5]

"Manufacturing a car or an iPad is a complicated task that requires a dizzying number of components."

A series of isolated incidents both related to COVID-19 and not have contributed to shipping delays. Most famously, the Suez Canal blockage shut down traffic in one of the world’s largest and most important shipping lanes. China’s aggressive attempts to eradicate COVID-19 has led to several port closures, including the massive port in Yantian.

The modern supply chain is extremely complex. Manufacturing a car or an iPad is a complicated task that requires a dizzying number of components. An automobile or electronics manufacturer may get parts from hundreds of suppliers located in five different continents. A delay in the manufacturer’s receipt of just one component can stall or slow production for weeks, leading to increased shortages. In such a complex system, any one of these factors discussed is sufficient to derail much of modern manufacturing. The fact that all these issues happened in quick succession is responsible for the current backups.

Effects

These disruptions in the supply chain have caused a series of developments for the U.S. economy. The labor and transportation challenges mean that products are stuck in the wrong places. In early October, the Port of Savannah, the third largest port in the country, nearly 80,000 shipping containers were stacked, more than 50% above normal levels.[6] These containers are filled with materials for manufacturing or finished goods ready for retailers, but backed-up shipping and a shortage of truckers have stranded them at the Port. That couch, for which you are waiting, may very well be stuck in one of those containers. The stress has driven shipping prices higher, with shipping giant Maersk’s average freight rate up 63% since 2019Q2.[7]

"The labor and transportation challenges mean that products are stuck in the wrong places."

When demand is up but logistics are delayed, product inventories are decreased. Inventory-to-sales ratios dropped to 33 days in October 2021 compared to 43 days in February 2020. Inventories of cars dropped to one month worth of sales versus two pre pandemic. Housing inventories dropped to 4.4 months of home sales versus 5.5 months pre pandemic.[8]

In response to labor shortages and demand increase, many companies are raising worker pay. Recently Roehl Transport, a Wisconsin trucking company, raised the average pay for its 2300 drivers by 9 to 11 percent.[9] Amazon is attempting to hire 75,000 new workers in North America at an average starting rate of $17 per hour with a signing bonus of up to $1,000.[10]

The shortage of goods, logistics complications, and rising labor costs have driven prices higher. The Personal Consumption Expenditures price index, the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation, consistently shows that prices are 4.0-4.4% higher than 2020.[11] The Consumer Price Index shows that prices for all items have increased 6.0% over pre-pandemic levels.[12] Those who have recently tried to buy a car recently should be particularly aware of these dynamics. About half of the CPI increase comes from the prices of new, used, leased, and rental automobiles.[13]

Will inflation last? In late October, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said that the supply chain problems mean inflation will persist but expressed confidence that industry would remedy these problems so that prices could stabilize in 2022.[14] However, some upward pressures suggest a different outlook. Workers who receive wage increases now are not likely to give back those raises when labor shortages stabilize, so that the price increases companies are implementing now to pay higher wages are here to stay. Some evidence exists that the wage raises thus far are merely redistributing workers already in professions like trucking rather than attracting new workers.[15] Another worrying trend is the sharp decline in national enrollment in community colleges, who provide much of the skilled labor that U.S. manufacturing requires. Fall 2021 National Student Clearinghouse data shows that enrollment in community colleges is down 14.1 percent since Fall 2019.[16] If a shortage of labor in key occupations continues, shipping will still be delayed, manufacturers may be unable to meet demand, and prices may continue to rise.

[1] FACT SHEET: Biden Administration Efforts to Address Bottlenecks at Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, Moving Goods from Ship to Shelf. Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/10/13/fact-sheet-biden-administration-efforts-to-address-bottlenecks-at-ports-of-los-angeles-and-long-beach-moving-goods-from-ship-to-shelf/

[2] 2021 Digital Economy Index. Available at https://business.adobe.com/resources/digital-economy-index.html

[3] Global demand isn’t booming. So why are shipping rates this high? Available at https://www.freightwaves.com/news/global-demand-isnt-booming-so-why-are-shipping-rates-this-high

[4] Global demand isn’t booming. So why are shipping rates this high? Available at https://www.freightwaves.com/news/global-demand-isnt-booming-so-why-are-shipping-rates-this-high

[5] “LA Port breaks cargo record again as 96 anchored ships wait and authorities scramble” Available at https://www.dailybreeze.com/2021/10/20/la-port-cargo-breaks-record-again-in-september-as-authorities-scramble-to-end-mammoth-backups/

[6] ‘It’s Not Sustainable’: What America’s Port Crisis Looks Like Up Close” available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/11/business/supply-chain-crisis-savannah-port.html?referringSource=articleShare

[7] Global demand isn’t booming. So why are shipping rates this high? Available at https://www.freightwaves.com/news/global-demand-isnt-booming-so-why-are-shipping-rates-this-high

[8] Why the Pandemic Has Disrupted Supply Chains. Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/blog/2021/06/17/why-the-pandemic-has-disrupted-supply-chains/#_ftn1

[9] Truckers are getting big pay hikes, but there's still a shortage of drivers. Available at https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/29/economy/truck-driver-shortage-pay-hikes/index.html

[10] Big companies follow big government. Available at https://finance.yahoo.com/news/big-companies-follow-big-government-morning-brief-100222592.html

[11] Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index. Available at https://www.bea.gov/data/personal-consumption-expenditures-price-index

[12] CPI Inflation Calculator. Available at https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

[13] Why the Pandemic Has Disrupted Supply Chains. Available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/blog/2021/06/17/why-the-pandemic-has-disrupted-supply-chains/#_ftn1

[14] Powell says inflation risks rising, but Fed can be ‘patient.’ Available at https://apnews.com/article/business-economy-prices-inflation-jerome-powell-e40680fde1db7758d1508c80701acde6

[15] Truckers are getting big pay hikes, but there's still a shortage of drivers. Available at https://www.cnn.com/2021/05/29/economy/truck-driver-shortage-pay-hikes/index.html

[16] Community College Enrollment in Fall 2021 and Cumulative Enrollment Impacts. Available at https://www.richmondfed.org/research/regional_economy/regional_matters/2021/rm_11_12_2021_community_college

Subscribe to the Weekly Economic Update

Subscribe to the Weekly Economic Update and get news delivered straight to your inbox.