Since President Trump took office, trade policy has been an essential component of his overall economic agenda, in addition to tax cuts and regulatory changes.

After passing the tax cut legislation in 2017, the administration started implementing major changes to trade policies in 2018 with goals of reducing the U.S. trade deficit and generating jobs in America. For example, the administration re-negotiated the trade agreement with Mexico and Canada (USMCA Agreement) to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The administration also raised tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from many countries in the first half of 2018.[1] In the second half of 2018, the administration targeted Chinese imports by imposing tariffs on a wide range of products; and the trade disputes between the two countries are still ongoing.

The trade dispute with China has gradually escalated. In July, the U.S. imposed a 25% tariff on $34.0 billion of imports from China (Figure 1). China retaliated with a 25% tariff on $34.0 billion of imports from the United States. In August, the United States imposed a 25% tariff on $16.0 billion of imports from China, and China again responded with a 25% tariff on $16.0 billion of imports from the United States. In September, the U.S. imposed a 10% tariff on $200 billion of Chinese imports, which was set to increase to 25% in January 2019. In response, China imposed 5% to 10% tariffs on $60 billion of imports from the United States.

During the recent Group of Twenty (G20) summit in Argentina, however, China and the United States agreed to delay the implementation of a 25% tariff set to be implemented in January 2019 for 90 days. Based on the trade volume between the two counties, close to half of the imports from China, and 85% of U.S. exports to China are subject to higher tariff rates than they had been in early 2018 after three rounds of tariff increases.

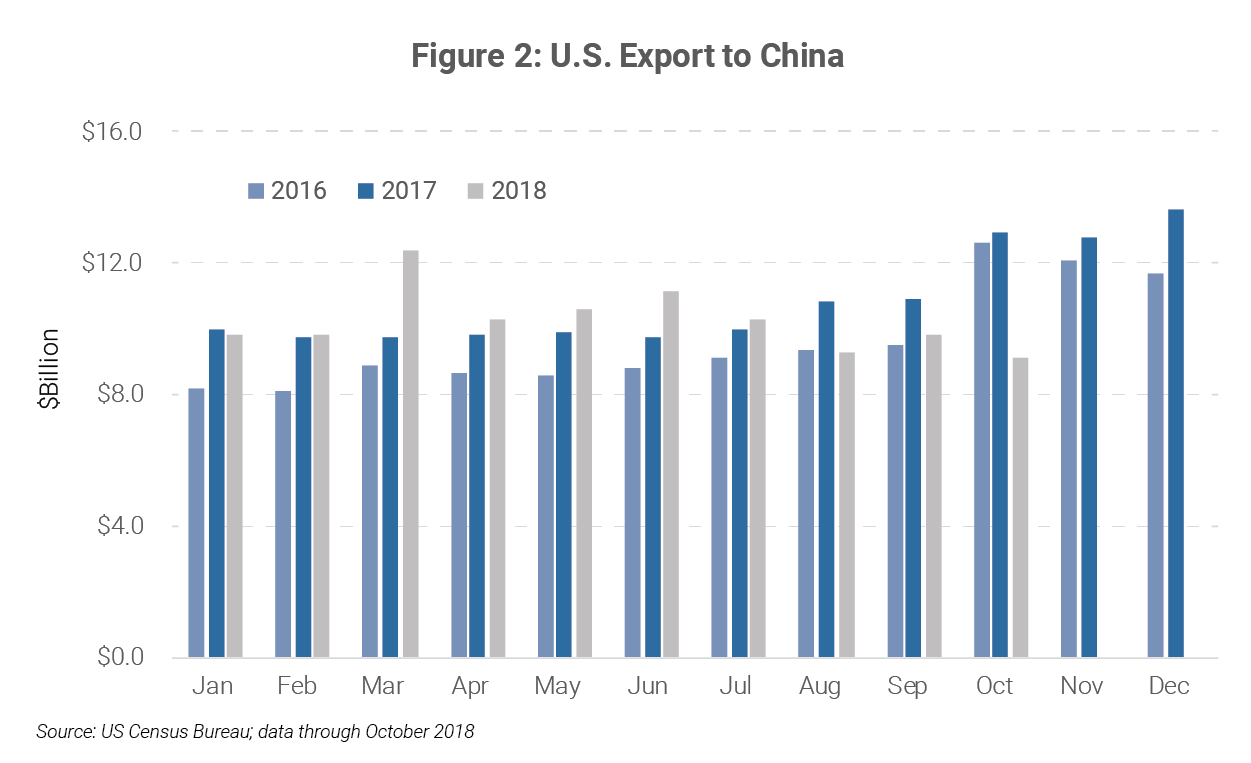

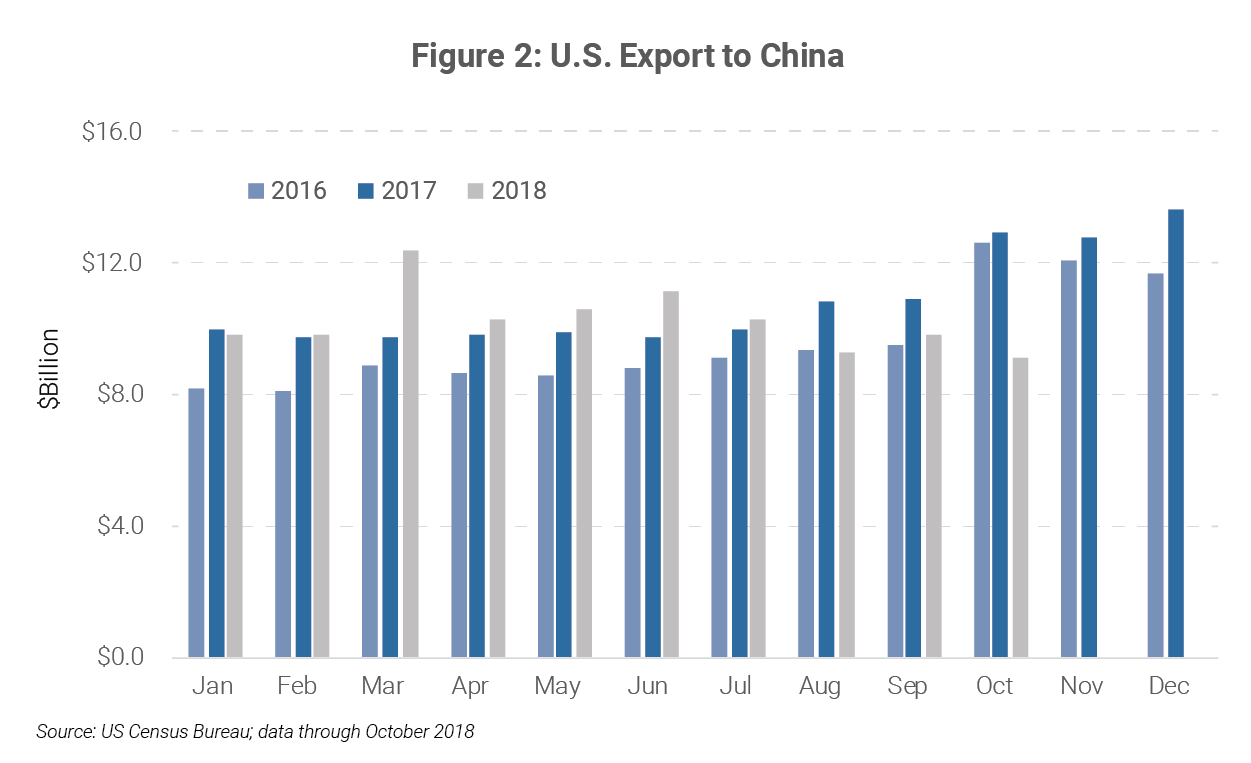

The imposition of tariffs on both sides affects the trade flows between the two countries. U.S. exports to China were affected immediately after China started increasing tariffs on U.S. goods and services. As shown in Figure 2, from January to July 2018, U.S. exports to China registered noticeable growth (average 8%) over the same months in 2017, but experienced sizable drops in the next three months from August to October. Total exports for the last three months were $28.2 billion in 2018, down from $34.7 billion for the same period last year, a 19% decline.

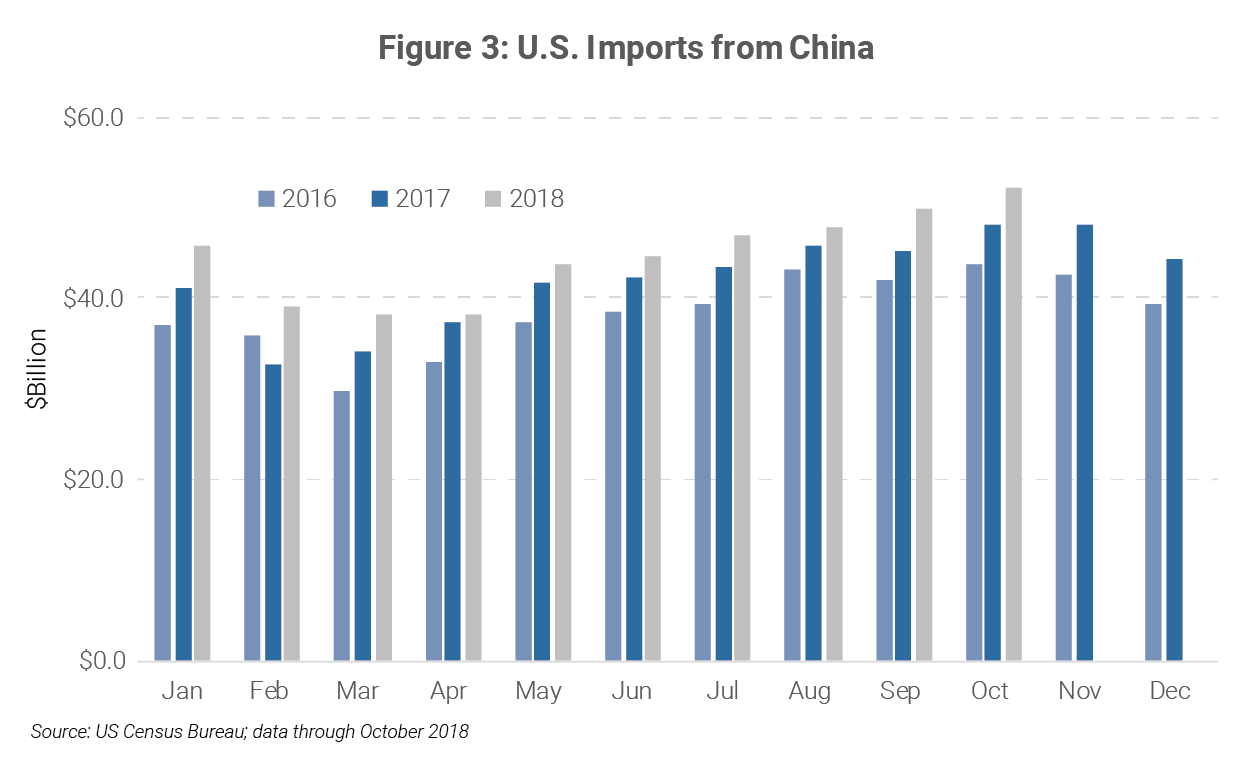

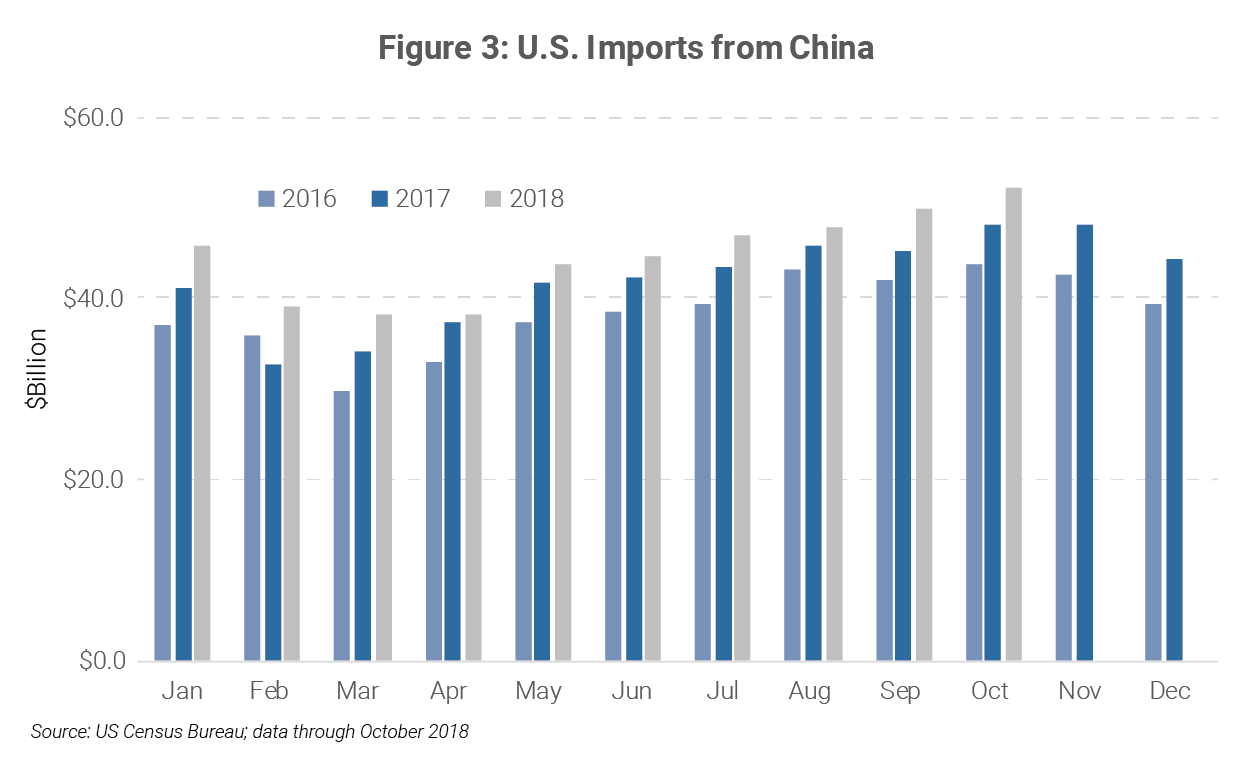

Paradoxically, imports from China to the United States did not decline despite the increased tariffs. As Figure 3 shows, imports from China exceeded their 2017 levels for every month in 2018, even after the imposition of U.S. tariffs in July. While higher imports in the months prior to the tariff increase can be explained by U.S. importers increasing their buying in anticipation of higher tariffs, the robust import growth since then suggests other factors are offsetting the tariff increase from the United States.

The possible reason is China’s exchange rate policy. To blunt the significant increase in tariffs on its exports to the United States, the Chinese government has resorted to devaluing their currency (Yuan). Unlike other major currencies such as the U.S. dollar, Euro, or British Pound, the exchange rates between the Chinese Yuan and other currencies are not entirely determined by market forces. Instead, the Chinese government exerts enormous control over the exchange rate of its currency.

The devaluation of the Chinese currency makes exports to the U.S. cheaper. For example, when the U.S. imposes a 10% tariff on a product, the dollar price faced by U.S. importers and subsequently consumers could rise by 10%, which would lead to less demand for the product. However, if the Chinese Yuan is devalued by 10%, U.S. importers and consumers will face essentially similar prices in dollars, which can help stabilize the demand for the Chinese product.

As Figure 4 shows, since April 2018, the value of the Chinese Yuan with respect to U.S. Dollar has depreciated 8.3%. That means that, other things equal, Chinese exports could be 8.3% cheaper in the U.S. market. The devaluation of the Chinese Yuan may have prevented a sharp price increase in imports from China thereby reducing the decline in imports from China.

Trade wars are complicated matters, and tariffs are not the only arsenal for the governments involved. Just as the Trump Administration wants to create jobs in the United States, the Chinese government does not want to see its export sector suffer, which may lead to massive job losses and social unrest. As a result, in addition to increasing tariffs on imports from the United States, China also utilized its currency tool to offset the negative impact of the tariff increase.

The prolonged trade dispute between China and the United States not only affects trade flows, but also the stock market, consumer spending, and other parts of the global economy.

[1] In March 2018, the 25% tariff took effect, with exemptions for the European Union, Canada, Mexico and some other countries. Beginning in June 2018, imports from the European Union, Canada, and Mexico were also subject to such a tariff.