Since assuming office in January, the Trump Administration has taken steps to enact policies with a wide range of impacts in the areas of healthcare, environment, immigration, and the economy. Economic policies have not been at the front and center of the media or public discourse lately, but understanding what may come is still extremely important. Potential changes in economic policies may include personal income tax cuts, corporate tax reform, and federal budget shifts, each of which can be quite complex. In this blog, we take a closer look at the different proposals for corporate tax reform.

During the 2016 campaign, then presidential candidate Trump promised to enact a straightforward cut on the corporate income tax rate, from the current 35% to 15%. Corporate income tax is applied to the profit portion of business income. Profit is defined as the net income of a business, equaling total revenue minus total cost. Examples of costs are state and local taxes, intermediate goods and services, wages and benefits for labor, and interest payments.

The Trump plan also attempts to address the issue of profit offshoring, where companies leave overseas profit abroad to avoid paying U.S. corporate income taxes. His plan will allow companies to move profits to the United States by taxing them at a much lower 10% rate. A straightforward reduction in the corporate tax rate will reduce tax revenue in the short term. Consequently, the federal government either needs to cut spending or allow the deficit to increase.

A different proposal circulated by House Speaker Paul Ryan and House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady attempts to address some of the same issues with the current corporate tax. Their plan would change the corporate income tax in five significant ways:

- Lower the tax rate to 20%.

- Businesses will be able to fully write off capital investments in the year they purchased them instead of depreciating them.

- Profits earned overseas by businesses would no longer be taxed.

- Interest would no longer be deductible as a business expense.

- The corporate tax would be “border adjusted.”

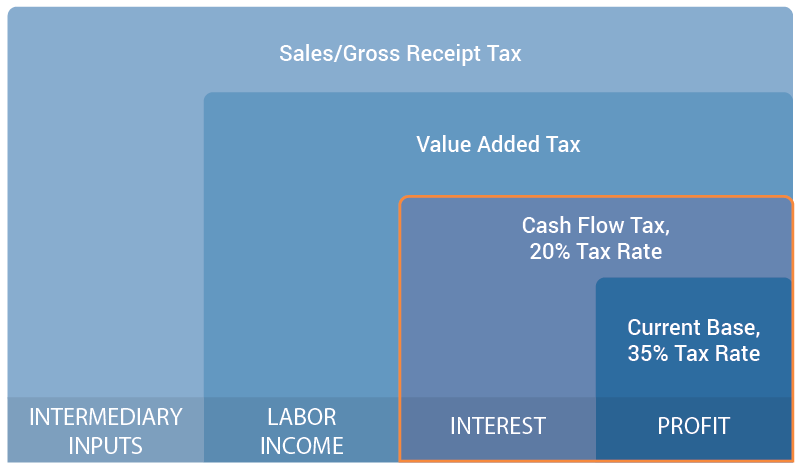

Together, these changes turn the corporate income tax into a “destination-based cash flow tax (DBCFT).” As shown in the red border in the above diagram, the tax base of DBCFT is broader than the current corporate income tax because it will tax interest expenses which are exempt from the current corporate income tax which only applies to profit. By lowering the tax rate but broadening the tax base, the Ryan-Brady plan attempts to avoid a sharp decline in tax revenue that could result from a simple rate cut.

To address the issue of profit offshoring, the Ryan-Brady plan proposes to tax the cash flow differentiated by destination. Only cash flows generated domestically will be subject to DBCFT, which means companies can move their overseas profits back to the United States without being hit with a huge tax bill. Similarly, exporters will benefit from the DBCFT as their revenues from abroad will be exempt.

Though the proposed cash-flow tax has a broader base than the current corporate income tax, it is not a value-added-tax (VAT). As the above diagram shows, VAT applies to the value-added portion of the business revenue. Since a large portion of value-add is labor income, a VAT has a much broader tax base than DBCFT. Finally, the broadest business tax is a sales or gross receipt tax, which is a tax on total business revenue without allowing a deduction for intermediary inputs.

The much-discussed border-adjustment-tax (BAT) can fit into the DBCFT framework. For importers, the Ryan-Brady plan proposes that the value of imported goods will not be exempt from this tax. Thus, corporate tax is adjusted at the border to become the border-adjustment-tax for importers.

At this time, it is not clear which type of corporate tax will be enacted into law. The DBCFT is a major tax change in the U.S. tax system that would affect all businesses in the country. Policymakers may choose to implement a narrowly focused DBCFT, or the border-adjustment-tax, applying only to importers. Or they may combine BAT with a traditional cut of corporate income tax rates, like the Trump plan, using BAT to offset revenue lost due to the tax cut on profits. Regardless, policymakers have a wide range of options to choose from in terms of corporate tax reform, from a broad-based gross receipt tax, to a narrowly focused tax on profits, or something in between.